Japan at a Crossroads: Yokosuka vs. Kawasaki

Pigs and Battleships uses the contrast between Yokosuka and Kawasaki to show how post-war American occupation trapped many Japanese people in cycles of dependency, crime, and exploitation.

Haruko’s eventual departure illustrates that the most promising path forward for Japan came from pursuing domestic industrial growth rather than remaining tied to the informal, U.S., dependent economy that shaped Yokosuka.

Postwar Yokosuka Through Imamura’s Lens

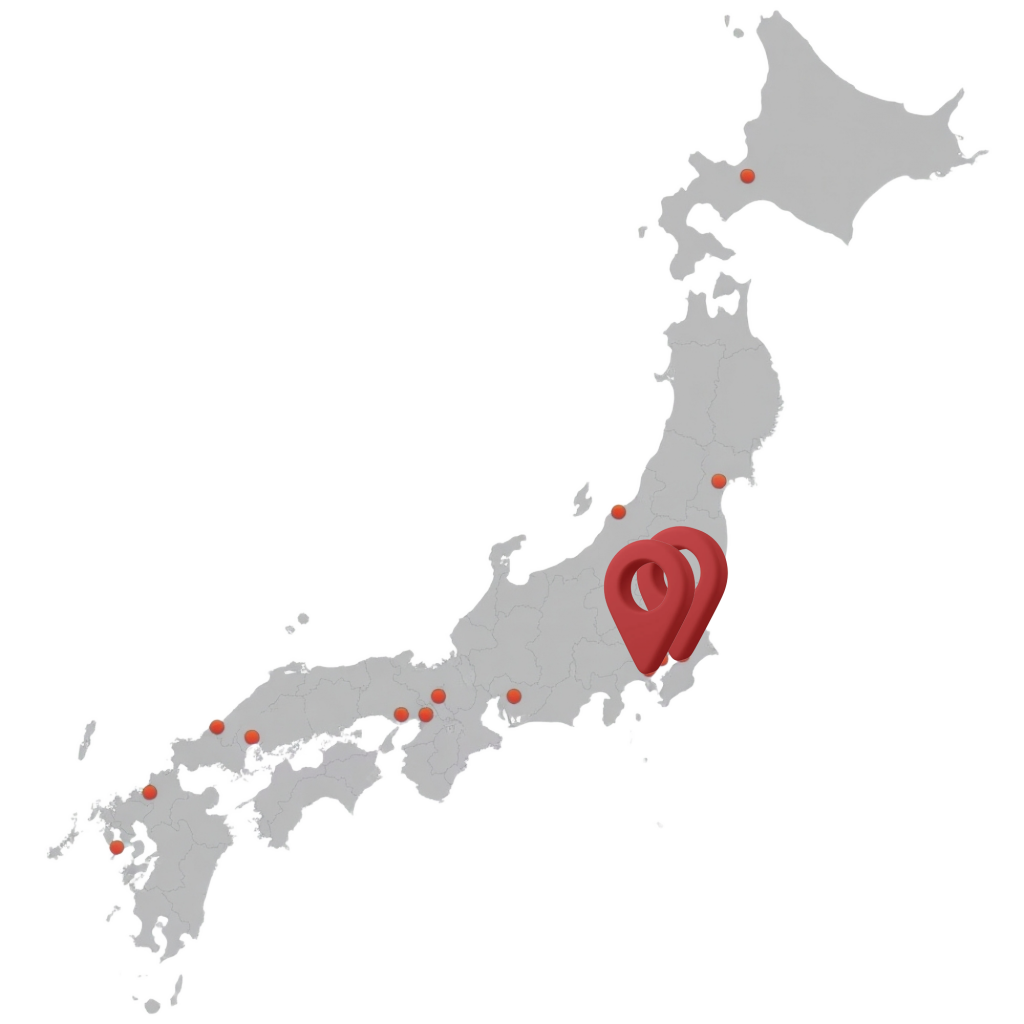

Pigs and Battleships (1961), directed by Imamura Shōhei, is set in the port city of Yokosuka about a decade after the U.S. occupation.

The film follows Kinta, a young gangster involved in a pig-smuggling ring tied to the American naval base, and Haruko, who hopes to escape to the industrial city of Kawasaki for a more stable future. Yokosuka represents a chaotic economy shaped by U.S. presence and crime, while Kawasaki symbolizes Japan’s new path of industrial growth.

Through satire and violence, the film portrays how postwar dependence on the U.S. traps ordinary people, making Haruko’s departure a rare chance for real change.

Japan After WWII: Uneven Recovery & U.S. Influence

After World War II, the Allied powers chose to occupy Japan in order to guide its recovery in a direction which suited their interests. In reality, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) —referring to General Douglas MacArthur and the entire bureaucracy of the occupation — was an American effort which “took orders from the U.S. government and paid scant attention” to the other powers or governing bodies (Gordon 229).

Working through the existing Japanese bureaucracy, SCAP initially made enormous changes to Japan’s established order and “sent a clear message that democracy should be the cornerstone of a new Japan” (Gordon 230). It also demilitarized Japan. Though Japan no longer had its own military, American military presence in the country was widespread.

Two years into the occupation, after shifting focus toward economic recovery, SCAP became less concerned with reforming traditional institutions. Realizing that labor reform and the complete overthrow of the zaibatsu (family-owned conglomerates) might not be in the best interest of fast economic recovery, they allowed the status-quo to continue in some sectors of the socio-political and economic landscape (Gordon 235-236). This shift toward conservatism soon took an even bigger leap back in response to the emerging Cold War and conditions elsewhere in Asia (Gordon 239). Such a shift was arguably not in the best interest of working-class Japanese, who were already suffering greatly from food shortages, inflation, and other consequences of the war.

Though the occupation officially ended in April 1952, American military presence in Japan remained high. The U.S. used Japan as a base for ongoing military action in Korea, and the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty “granted the United States the right to keep bases and troops in Japan” (Gordon 242). The Korean War initiated an era of rapid economic growth, during which “Japan changed from a site of destruction and poverty to a place of prosperity,” but “benefits were unevenly distributed” (Gordon 245).

This uneven distribution can be seen clearly in Pigs and Battleships. Yokosuka, where the action of the film takes place, feels trapped in the post-war era, with the shadow of the occupation everywhere. American military presence defines the socio-economic condition of the city. When discussing the pig farm, Kinta suggests that Japanese residents still do not have access to sufficiently nutritious food. The town’s residents survive by serving the U.S. troops — providing them with food, sex, and all other manner of black-market entertainment. Kawasaki, meanwhile, holds the promise presented by the “economic miracle” (Gordon 245) which began in the 1950s. In ending the film with Haruko’s bold departure for Kawasaki, Imamura argues that Japan and its people should take control of their own future and continue moving away from the indignities of the post-war era.

Linking Film to History

Choosing a Path Forward

Pigs and Battleships depicts a Japan divided between dependence on U.S. military influence in Yokosuka and new opportunities in industrial centers like Kawasaki. Kinta’s death and Haruko’s departure highlight that remaining in exploitative systems leaves little hope, while seeking change offers the chance for stability and dignity.

By reflecting real postwar conditions, uneven recovery, U.S. presence, and working-class struggle, the film reveals how Japan’s future depended on ordinary people deciding which path to take.